Once upon a time, before angled decks, it was important to differentiate the barricade from the barriers, which are no longer needed on angled-deck carriers.

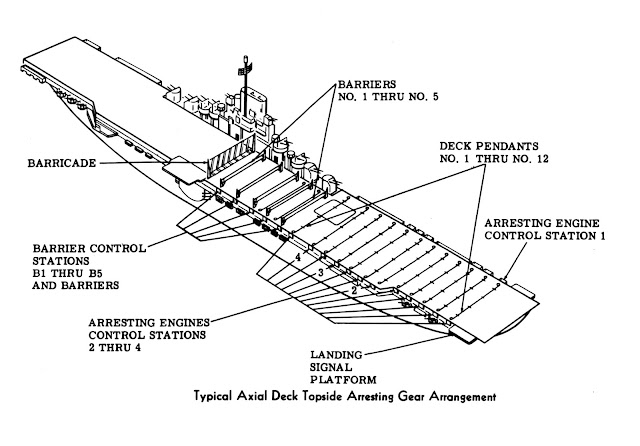

This is an illustration of the usual arrangement of cross-deck pendants, barriers, and the barricade on an Essex-class carrier:

Note that there are 12 cross-deck pendants (the last one of which goes across the elevator; it had to be pulled forward when the elevator was needed), five barriers, and one barricade. There are four control stations for the cross-deck pendants and one each for the five barriers. An enlisted man is assigned to each control station. In the case of the barriers, one of his responsibilities is to raise and lower his barrier as required, notably prop barriers to be up for prop plane approaches and down for jet approaches; Davis barriers are the reverse.

The difference between the original barrier and the Davis barrier is important. For a refresher, see https://thanlont.blogspot.com/2010/10/barriers-and-barricades-one-more-time.html

It was also important, in the event that the hook caught a late wire and a trap seemed assured, that the aft-most barrier be lowered if an arrestment seemed assured so the plane did not engage it, possibly causing damage to the plane and likely disrupting the flow of landings, delaying them.

This is a pretty good example of a late trap by an F9F Panther that also resulted in a barrier engagement. The prop barriers are down and the Davis barriers, up. Note that the hook did catch a late wire/pendant but the first Davis barrier was still up. The plane's nose landing gear snagged its activator strap appropriately (there was also a retractable post immediately in front of the windscreen to activate the barrier in the event of a nose landing gear collapse).

Also note that in this instance, the Davis barrier cables (as opposed to the canvas activator straps) did not engage the main landing gear struts, which was how the jet was to be brought to a stop by the Davis barrier. That was because there was an engagement "window" with respect to the airplane's speed. Too slow, and the cables fell back to the deck before the main landing gear got to them; too fast, and the cables had not yet been pulled up high enough to clear the wheels and snag the struts (this latter case resulted in the addition of the barricade to the mix).

Every once in a while, someone posts a picture of a barricade

engagement on an angle-deck carrier and refers to it as the barrier.

Sometimes I comment that it is properly known as the barricade, not

barrier, and the poster or someone else is offended at being incorrectly

corrected. However, as far as I know, it is still officially designated the barricade in the current CV-NATOPS manual as it was in July 2009.